Assassin Bug – Zelus luridus

Adult assassin bugs range from 4-40 mm, with an elongated head and distinct narrowed neck, long legs, and a prominent, segmented tube for feeding (rostrum).

Assassin bugs use their rostrum to inject a lethal saliva that liquefies the insides of the prey, which are then sucked out by means of a cybarial pump through another passage in the rostrum. The legs of some species are covered in tiny hairs that help them hold onto their prey while they feed. As nymphs, some species will cover and camouflage themselves with plant debris, or the remains of dead prey insects [1]. Some species have been known to feed on cockroaches or bedbugs (in the case of the masked hunter) and are regarded in many locations as beneficial. Some people breed them as pets and for insect control. Some assassin bug groups specialize on certain prey groups, such as ants (feather-legged bugs – Holoptilinae), termites, or diplopods (Ectrichodiinae).

Reduviid bugs in the genus Triatoma, commonly called triatomine bugs, kissing bugs, or cone-nosed bugs, can carry the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi that causes Chagas disease, also referred to as American trypanosomiasis. Triatomines are primarily nocturnal and feed on the blood of mammals (including humans), birds, and reptiles.

Chagas disease is named after the Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas, who discovered the disease in 1909. It is transmitted to animals and people by insect vectors that are found only in the Americas. In the United States, Chagas disease is considered a Neglected Infection of Poverty (NIP), since it is found mostly in those with limited resources and limited access to medical care.

Infection is most commonly acquired through contact with the feces of an infected triatomine bug, but can also be passed from mother to baby, by contaminated blood products, organ transplants, or, rarely, through contaminated food or drink. [2]

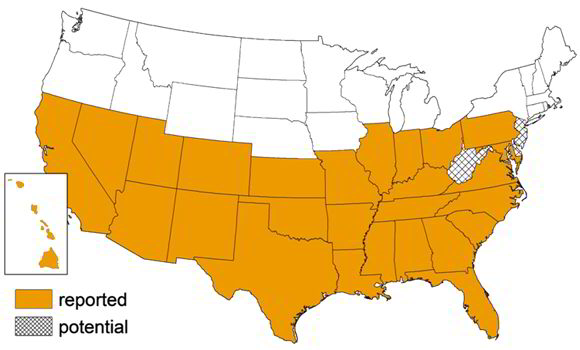

Triatomine bugs are currently found over the lower 2/3rds of the U.S., including Hawaii. Their range is expanding rapidly due to climate change, and they can live indoors and in a variety of outdoor venues: in chicken coops, dog houses, in rodent nest or animal burrows; in rock or wood piles, beneath the bark of trees, or under concrete walkways and patios.

Triatomine bug range in United States [2]. Map courtesy CDC

Because most indoor structures in the United States are built with insect-resistent sealed entryways, triatomine bugs rarely infest indoor areas of houses. However, in areas of Latin America where human Chagas disease is an important public health problem, the bugs nest in cracks and holes of substandard housing, i.e. those with thatched roofs or mud walls.

Discovery of immature stages of the bug (wingless, smaller nymphs) indoors may be an indication of infestation; they are likely to be in one of the following settings: in pet bedding, areas of rodent infestation, and in bedrooms, especially under or near mattresses or night stands. In fact, the larvae of the assassin bug Reduvius personalis is one of the known predators of the human scourge, bed-bug Cimex lecticularis [1].

Transmission of Chagas disease from a bug to a human is not easy. The parasite that causes the disease is in the bug feces. The bug generally defecates on or near a person while it is feeding on his or her blood, generally when the person is sleeping. Transmission occurs when fecal material gets rubbed into the bite wound or into a mucous membrane (for example, the eye or mouth), and the parasite enters the body [2].

|

|

Romaña’s sign: Swelling of the eyelid is a marker of acute Chagas disease. The swelling is due to bug feces being accidentally rubbed into the eye, or because the bite wound was on the same side of the child’s face as the swelling. [3] |

It is important to note that not all triatomine bugs are infected with the parasite that causes Chagas disease. The likelihood of getting Chagas disease from a triatomine bug in the United States is low, even if the bug is infected [2].

References

- James Rennie, Insect Architecture, Vol 2. pg. 165 “Structure of Larvae”

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Parasites – American Trypanosomiasis, or Chagas Disease”