Bees, Wasps & Ants – Order Hymenoptera

Hymenopterans inhabit a wide variety of habitats, and show an incredible diversity in size, behavior, structure and color. The social colonies formed by bees and ants are among the most complex societies on earth, which may contain millions of individual insects; all programmed with a simple ruleset that describes their every motion through every stage of their lives. Leaderless. Commanded and guided with pheromones and other communicative chemicals generated by her peers and her queen, these little suckers are indeed masters of their environment. They practice sustainable agriculture and only use renewable resources and have for millions of years.

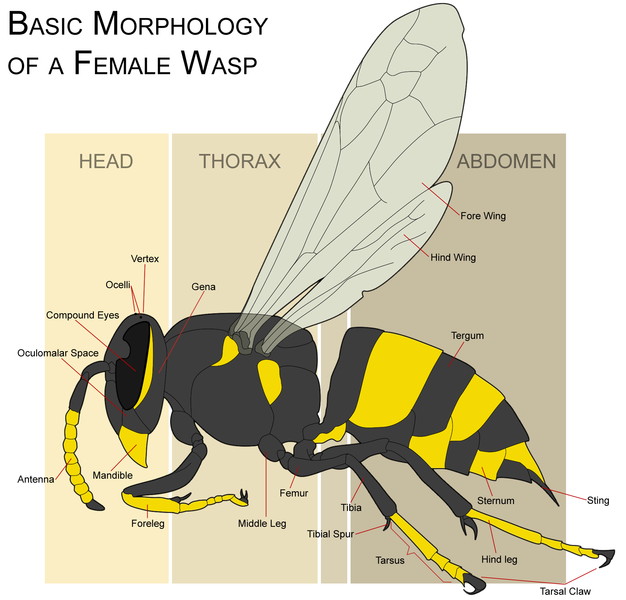

Most hymenopterans are happiest and most active on warm, sunny days, but there are those on the dark side, nocturnal or crepuscular. All adults have chewing mouthparts; bees and some wasps have modified tongue-like structures for drinking liquid nectar. Winged species have four membranous wings which can be hooked together in pairs during flight.

Aculeata – Bees, Ants and Stinging Wasps

Aculeata, from Latin aculeus, sting, needle. The evolutionary modification of the ovipositor (egg-layer) into a stinger (and venom-delivery system in some species) unites this taxon. Not all aculeates can sting, and some aculeates have ovipositors instead of stingers. Go figure.

All social bees and wasps use their stinger to defend the colony. The sting consists of a venom reservoir and three “needles”: two lancets (sometimes barbed) and a stylet, linked together to form a hollow tube through which venom can be pumped. The stylet makes the initial penetration, and then the two lancets, which slide on “rails” alongside the stylet come forward to deepen the wound.

Wasps and bumblebees can withdraw the stinger and reuse it, but bees have barbs on their sting; they cannot be withdrawn and the bee sacrifices herself for the colony: when she withdraws, the venom sacs are pulled from her abdomen. The venom apparatus continues to function, however, pumping venom into the wound long after the fatally wounded bee has departed.

Some families represented in our collection:

Family Vespidae – Yellowjackets, Paper Wasps, Hornets, Potter, Mason and Pollen Wasps

Family Formicidae – Ants

Family Halictidae – Halictid Bees

Family Andrenidae – Andrenid & Mining Bees

Family Apidae – Cuckoo, Carpenter, Digger, Bumble & Honey Bees

Family Sphecidae – Thread-Waisted Wasps, Mud Daubers

Family Pompilidae – Spider Wasps

This eastern yellowjacket worker is exiting her underground nest. As she begins the transition to flight, the fore and hindwings get hooked together and so act as one large thrust-generating surface, much like a modern aircraft extending its flaps. This larger surface is more efficient. The wings are unhooked automatically when the creature alights so they can be kept out of the way folded back over the abdomen.

Symphyta – Sawflies, Horntails and Wood Wasps are considered the most primitive of the Hymenoptera. Adults are often mistaken for wasps, but a crucial difference is the lack of the narrow “waist” found in the bees, wasps and ants.

Horntails, or wood wasps are so-called for their spike-like ovipositor, which they use to pierce tree bark and wood wherein they lay eggs. The resulting larvae, living within the wood are in turn prey for their sister hymenopterans in the parasitic Apocrita, esp. Ichneumonidae, which use famous wood-penetrating ovipositors of their own to lay eggs on the unfortunate host.

Sawflies get their name from the saw-like nature of their ovipositor. Sawfly larvae usually feed on the outside of plants, many prefer grasses, but some do serious damage in the timber industry as woodborers and leaf miners. This female is using her saw to slit open blades of grass wherein she lays her eggs. It took me many attempts before I was able to capture this process. It is virtually impossible to tell what is going on while these creatures are laying eggs, it’s so quick, and the structures involved are so small. Early springtime (mid-April) is the time to stalk these enchanting insects – I found many of these sawflies (Dolerus nitens) laying eggs in my lawn at Oregon, Illinois.

I found this huge male ichneumon wasp (Above: subfamily Anomaloninae) as he hunted the forest understory for females. He flitted through the shadows in a bouncing flight; the black wings and black body become quite invisible, and all you see is the yellow antennae and yellow hind legs as 2 pairs of tiny filaments dancing in thin air – it’s really a magical sight! I was lucky to catch him while he alighted to clean his abdomen with his back legs – the spurs on the rear legs are used to energetically scrape the abdomen in an (apparently successful) effort to dislodge eggs laid by other parasites. I’ve seen large Megarhyssa females spend more than 10 minutes cleaning their abdomens and ovipositors before flying off.

Parasitica – Parasitic Apocrita

This artificial grouping contains all the taxa not included in those other artificial groupings, Symphyta and Aculeata. Here are the wonderful parasitoids, including the Ichneumonidae, the Braconidae, Gasteruptiidae, Chalcid wasps; Family Agaonidae, the fig wasps; Cynipidae, gall wasps, and many others. Bugguide.net has a good listing of the relevant families and superfamilies: “Parasitica.”

Ichneumon Wasps

Ichneumonidae alone accounts for 4700 recognized valid species, making it hands down the largest family of North American insects [3]. Represented in our collection are superfamilies Chalcidoidea, Evanioidea, and Ichneumonoidea.

You can often see ichneumons and braconids hunting amidst low foliage; the females hunt for males and then hosts, the males hunt for mates and then they are finished. It’s not often you can catch one actually depositing eggs, but it’s a really wonderful thing to see; a marvel of efficiency that is the product of millions of years of evolution.

You can see a complete series of photos of the egg-laying process HERE.

Ovipositors are usually well developed and modified into a stinger in the Aculeata, commonly considered the highest form of the Order. All social wasps use their stinger to defend the colony. Many humans are allergic to bee stings, and can suddenly develop anaphylactic shock, a condition which can kill if not treated quickly.

Allegheny mound ants are named for their large, conspicuous nests which can be 2 meters or more across and a meter high. They are native to eastern North America from Nova Scotia to Georgia. The ants pictured here were resident in the Allegheny National Forest of northeastern Pennsylvania. AMA are aggressive foragers for protein in the form of arthropod prey, principally insects. They also obtain carbohydrates from ingesting sugar-rich honeydew excreted by aphids and tree & leafhoppers, which the ants cultivate, herd, and protect from predators.

AMA become pests with their extensive tunneling, and their unfortunate habit of killing plants near the nest by injecting formic acid into them. Even small trees and shrubs can fall victim. AMA will bite if disturbed, and an aggrieved colony can boil ants out an alarming rate. The ants use pheromones to alert each other to intruders.

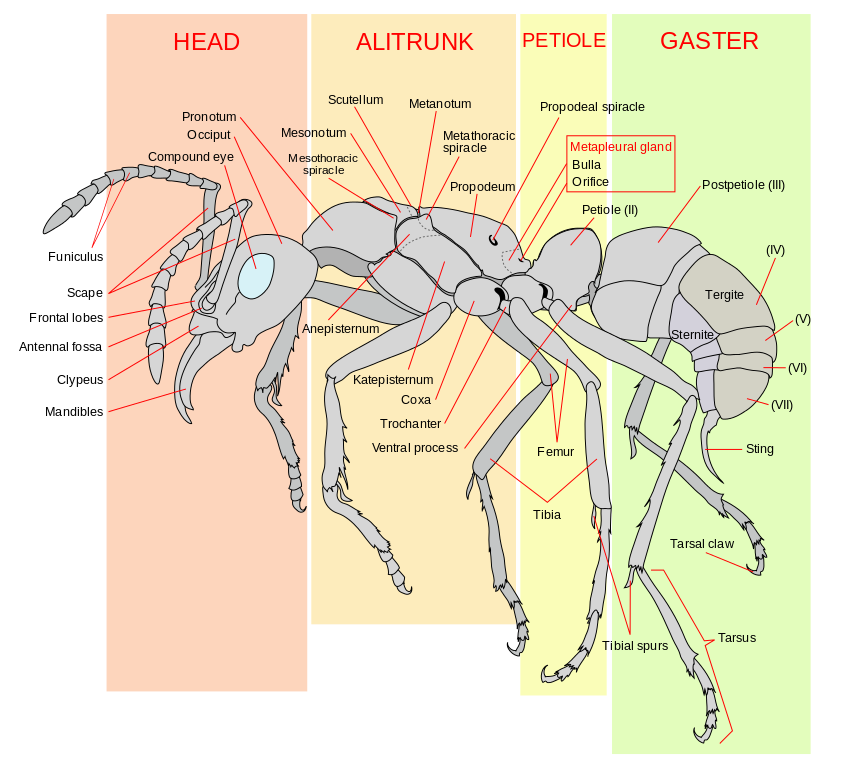

Ants are distinguished from other insects by the combination of elbowed antennae, a strongly constricted second abdominal segment forming a distinct node-like petiole, a wingless worker caste, and the presence of a metapleural gland. They can sense with organs located on the antennae, which can detect pheromones (single compounds) and hydrocarbons on the outer layer of the body (a set of different compounds). The latter is highly important for the recognition of nestmates from non-nestmates.

Recent research suggests chemicals on ants’ feet tranquilize and subdue colonies of aphids, keeping them close by as a ready source of food. The study sheds new light on the complex symbiotic relationship between the ants (order Hymenoptera) and aphids, hugely destructive insects in the order Hemiptera.

It has long been known that certain types of aphids are herded and farmed by ants, and that the ants offer protection from other insect would-be predators (ladybugs and their larvae are perhaps the most prolific), in exchange for honeydew, a sugary secretion the ants eat. Ants have been known to bite the wings off the aphids in order to stop them from flying away with one of ants’ staple foods.

Chemicals produced in the glands of ants can also sabotage the growth of aphid wings. The new study shows that ants’ chemical footprints also play a key role in manipulating the aphid colony, keeping it sedentary. “We believe that ants could use the tranquillizing chemicals in their footprints to maintain a populous ‘farm’ of aphids close their colony, to provide honeydew on tap. Ants have even been known to occasionally eat some of the aphids themselves, so subduing them in this way is obviously a great way to keep renewable honeydew and prey easily available.”

Ants are not the only hymenopterans taking advantage of aphids. This tiny wasp (3mm) is laying eggs on them. The wasp would approach the aphids with its abdomen and ovipositor pointed / folded underneath (It was the only time she walked slowly enough that I could follow her movement), and then rush forward while extending her abdomen even farther, and give an aphid a quick poke. The poke only takes a second or two, tops. She seems genuinely intent on staying away from the aphids, although the aphids didn’t react to her presence at all, even when she poked them. None of the aphids had even exuded that orange wax from their cornicles, as I’ve seen most every time aphids are under attack by lady beetles or their larvae.

Anyway, it was fascinating and I watched at least three or four of these girls ganging up on this aphid colony. I measured the aphids afterward: The smallest are 1mm and the larger ones go up to 3.5mm.